Growing Together - Children's Mental Health Week 2022

This week, for children’s mental health week, I’ve been sharing simple ways we can support children with their mental health and “grow together.”

I’ve been working with Motion Alley to create short animations called “Life In Lockdown” to help explore wellbeing themes with children.

Here’s Episode One, where I talk to SK8TR Boy about the things he’s missing and how he’s using his imagination to help him.

In Episode Two, Rainbow Girl tells us why it’s good to find ways to express your emotions.

Day 3: Be Mindful

This week it’s Children’s Mental Health Week (#childrensmhw) and, at ThinkAvellana, we’re sharing simple ways to boost wellbeing in children. We hope parents, grandparents, carers, teachers - and anyone else who cares for children and young people - will find them useful.

Our minds can be very busy, getting pulled into thinking about the past or worrying about the future. Finding ways to focus on what’s happening in the present moment is another way to build your child’s wellbeing.

Here are three different ways to help children develop their mindfulness skills, which will probably work best if you join in too (especially if it’s younger children involved).

1) Draw for 10 minutes

Give everyone a pencil and paper, set a timer for 10 minutes, and draw something you can see. Bring your attention to the shapes, colours, and patterns. Look at the object from different angles. Challenge older children to see if they can spot when their mind’s wandering (or wondering!) and bring their attention back to the drawing. This activity isn’t about how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ the drawing is, it’s about whether you can focus on the activity and bring your attention back when it wanders.

2) Take a bear for a ride

Younger children may enjoy this simple mindfulness technique for bringing attention to their breath. Ask your child to find their favourite small soft toy. Lay flat on the floor and invite them to put the soft toy on their tummy. Set a timer for two minutes, and ask them to watch how the toy moves up and down as they breathe in and out. This simple act of noticing the movement allows your child to remain “in the moment” for more than one moment.

3) Train the “puppy mind”

Older children (and adults) might enjoy watching this video from the Mindfulness In Schools Project. It’s a 10-minute mindfulness practice that uses a fun and playful animation.

If you’ve got other mindfulness based activities that work for you, your family or school, we’d love to hear about them. Join the wellbeing conversation on our Facebook page.

We’ve been sharing other ways to boost wellbeing in children on our blog here.

Day 2 - Be Grateful

This week it’s Children’s Mental Health Week (#childrensmhw) and, at ThinkAvellana, we’re sharing simple ways to boost wellbeing in children. We hope parents, grandparents, carers, teachers - and anyone else who cares for children and young people - will find them useful.

It can be easy to feel other people’s lives are better than our own, especially when we’re bombarded with perfect images on social media. We can get stuck thinking others are more beautiful, have more money and fun, or simply ‘have more’. And children are just as susceptible as adults to this comparison trap. So how can we help them (and ourselves)?

One idea is to bring attention to what’s working well in your/their life by developing gratitude skills. Here are three ways to do this:

1) Start a gratitude jar

Get children into the habit of writing a short gratitude note when things have gone well, and putting it into a gratitude jar. You can encourage them by modelling the behaviour and doing it yourself (it may boost your mood too!). To help get you started, there’s a 40 second video on our blog.

2) Write a gratitude journal

Older children may prefer to keep a gratitude journal, noting down the things they appreciate and the things that went well for them each day. It can include the positive moments they witnessed too - perhaps good things that happened to their friends that they want to celebrate and give thanks for.

3) Have a gratitude conversation

Find a time each day to chat about gratitude. Some parents like to do this before their child goes to sleep, prompting them to talk about what’s gone well that day. Some teachers build the chat into the end-of-school routine, by asking questions like ‘Tell me about someone who’s been kind to you today” or “Tell me about something you feel really thankful for today”.

Building gratitude habits doesn’t mean we diminish, or lack a response to, the struggles and difficult moments that children experience. These moments are really important to talk about too. But, having a time in the day when you focus on the positive can be useful in helping children to keep their thoughts balanced.

If you have a gratitude habit that works for your child, please do share it with us.

And in case you missed it yesterday, we talked about ways to help your children build their strengths.

Tomorrow, you’ll find even more ways to help your child build their wellbeing.

Here's our winter newsletter.

Sign up to our mailing list to get our newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Photo by Jessica Roberts - http://jessica-roberts.com

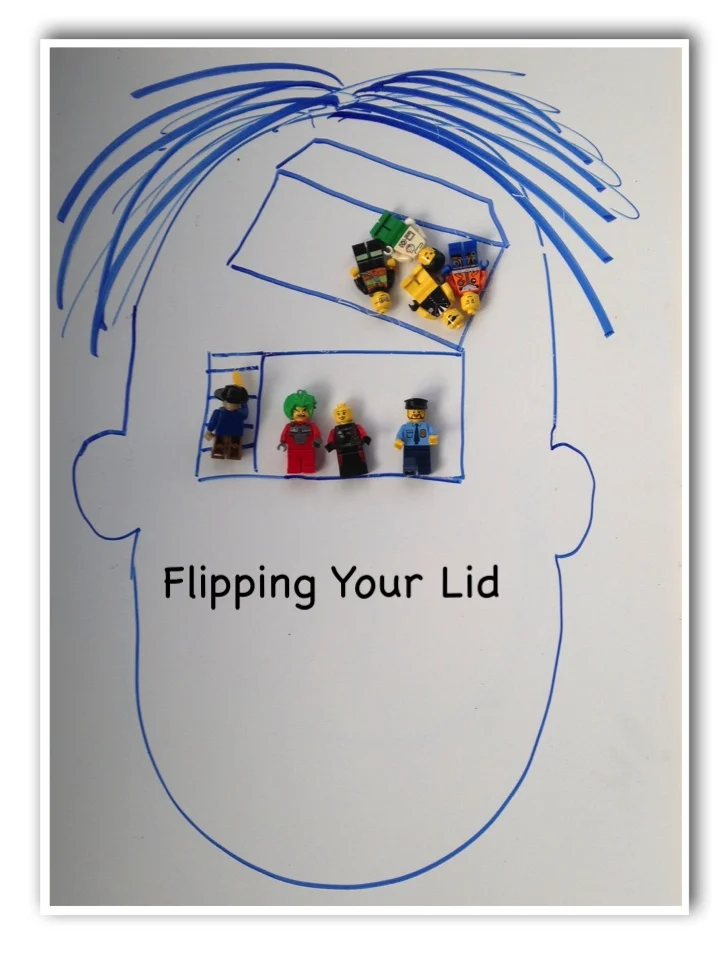

When children understand what’s happening in the brain, it can be the first step to having the power to make choices. Knowledge can be equally powerful to parents too. Knowing how the brain works means we can also understand how to respond when our children need our help.

Sometimes our brains can become overwhelmed with feelings of fear, sadness or anger, and when this happens, it’s confusing, - especially to children. So giving children ways to make sense of what’s happening in their brain is important. It’s also helpful for children to have a vocabulary for their emotional experiences that others can understand. Think of it like a foreign language; if the other people in your family speak that language too, then it’s easier to communicate with them.

So how do you start these conversations with your children, make it playful enough to keep them engaged, and simple enough for them to understand?

Here is how I teach children (and parents) how to understand the brain.

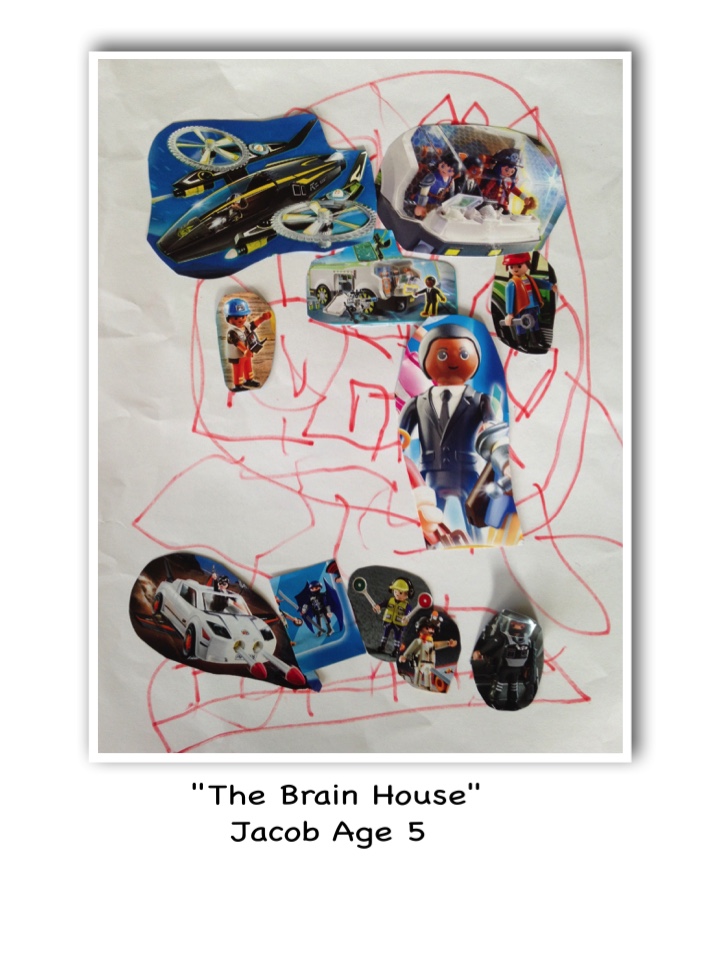

I tell children that their brains are like a house, with an upstairs and a downstairs. This idea comes from Dr Dan Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson's book "The Whole-Brain Child" and it’s a really simple way to help kids to think about what’s going on inside their head. I’ve taken this analogy one step further by talking about who lives in the house. I tell them stories about the characters who live upstairs, and the ones who live downstairs. Really, what I’m talking about are the functions of the neocortex (our thinking brain - the upstairs), and the limbic system (our feeling brain - the downstairs).

Typically, the upstairs characters are thinkers, problem solvers, planners, emotion regulators, creatives, flexible and empathic types. I give them names like Calming Carl, Problem Solving Pete, Creative Craig and Flexible Felix

The downstairs folk are the feelers. They are very focused on keeping us safe and making sure our needs are met. Our instinct for survival originates here. These characters look out for danger, sound the alarm and make sure we are ready to fight, run or hide when we are faced with a threat. Downstairs we’ve got characters like Alerting Allie, Frightened Fred, and Big Boss Bootsy.

It doesn’t really matter what you call them, as long as you and your child know who (and what) you are talking about. You could have a go at coming up with your own names: try boys/girls names, animal names, cartoon names or completely made-up names. You might like to find characters from films or books they love, to find your unique shared language for these brain functions.

Our brains work best when the upstairs and the downstairs work together. Imagine that the stairs connecting upstairs and downstairs are very busy with characters carrying messages up and down to each other. This is what helps us make good choices, make friends and get along with other people, come up with exciting games to play, calm ourselves down and get ourselves out of sticky situations.

Sometimes, in the downstairs brain, Alerting Allie spots some danger, Frightened Fred panics and before we know where we are, Big Boss Bootsy has sounded the alarm telling your body to be prepared for danger. Big Boss Bootsy is a bossy fellow, and he shouts ‘the downstairs brain is taking over now. Upstairs gang can work properly again when we are out of danger’. The downstairs brain “flips the lid” (to borrow Dan Siegel’s phrase) on the upstairs brain. This means that the stairs that normally allow the upstairs and downstairs to work together are no longer connected.

When everybody in the brain house is making noise, it’s hard for anyone to be heard. Bootsy is keeping the upstairs brain quiet so the downstairs folk can get our body ready for the danger. Boots can signal other parts of our body that need to switch on (or off). He can make our heart beat faster so we are ready to run very fast, or our muscles ready to fight as hard as we can. He can also tell parts of our body to stay very very still so we can hide from the danger. Bootsy is doing this to keep us safe.

Try asking your child to imagine when these reactions would be safest. I often try to use examples that wouldn’t actually happen (again so that children can imagine these ideas in a playful way without becoming too frightened by them). For example, what would your downstairs brain do if you met a dinosaur in the playground?

Think of some examples to share with your child about how we can all flip our lids. Choose examples that aren’t too stressful because if you make your kids feel too anxious they may flip their lids then and there!

Here’s an example I might use:

Remember when Mummy couldn’t find the car keys and we were already late for school. Remember how I kept looking in the same place over and over again. That’s because the downstairs brain had taken over, I had flipped my lid and the upstairs, thinking part of my brain, wasn’t working properly.

There might be times when we flips our lids but really we still need the upstairs gang like Problem Solving Pete, and Calming Carl to help us.

We all flip our lids, but often children flip their lids more than adults. In children’s brains, Big Boss Bootsy can get a bit over excited and press the panic button to trigger meltdowns and tantrums over very small things and that’s because the upstairs part of your child’s brain is still being built. In fact, it won’t be finished being built until the mid twenties. Sometimes, when I want to emphasise this point, I ask kids this question:

Have you ever seen your Dad or Mum lay on the floor in the supermarket screaming that they want chocolate buttons?

They often giggle, and giggling is good because it means it’s still playful, so they are still engaged and learning. I tell them parents actually like chocolate just as much as children, but adults have practiced getting Calming Carl and Problem Solving Pete to work with Big Boss Bootsy and can (sometimes) stop him from sounding the danger alarm when he doesn’t need to. It does take practice and I remind children that their brains are still building and learning from experience.

Once you’ve got all the characters in the brain house, you have a shared language that you can use to help your child learn how to regulate (manage) their emotions. For example, ‘it looks like Big Boss Bootsy might be getting ready to sound the alarm, how about seeing if Calming Carl can send a message saying ‘take some deep breaths’ ’’ .

The language of the brain house also allows kids to talk more freely about their own mistakes, it’s non judgemental, playful and can be talked about as being separate (psychologists also call this ‘externalised’) from them. Imagine how hard it might be to say ‘I hit Jenny today at school’ versus ‘Big Boss Bootsy really flipped the lid today’. When I say this to parents, some worry that I’m giving children a ‘get out clause’ - ‘can’t they just blame Bootsy for their misbehaviour?’. Ultimately what this is about is enabling children to learn functional ways to manage big feelings, and some of that will happen from conversations about the things that went wrong. If children feel able to talk about their mistakes with you, then you have an opportunity to join your upstairs brain folk with theirs, and problem solve together. It doesn’t mean they escape consequences or shirk responsibility. It means you can ask questions like ‘do you think there is anything you could do to help Bootsy keep the lid on?’.

Knowing about the brain house also helps parents to think about how to respond when their child is flooded with fear, anger or sadness. Have you ever told you child to ‘calm down’ when they have flipped their lid? I have. Yet what we know about the brain house is Calming Carl lives upstairs and when Bootsy’s flipped the lid, Calming Carl can’t do much to help until the lid is back on. Your child may have gone beyond the point where they can help themselves to calm down. Sometimes, parents (teachers or carers) have to help kids to get their lids back on, and we can do this with empathy, patience and often taking a great deal of deep breaths ourselves!

Don’t expect to move all the characters into the brain house and unpack on the same day; moving house takes time, and so does learning about brains. Start the conversation and revisit it. You might want to find creative ways to explore the brain house with your child.

Here are a few ideas to get you started:

Illustration: "Bright Future" by Peter Knock

When I first saw Shawn Achor’s Tedtalk, I knew that something exciting was happening. I stopped everything. I watched it again. I rushed in from my office to show it to my husband. He watched it and at the end, smiled and said ‘Hey, he just said what you’ve been saying for the last few months’.

And this is what I’ve been saying:

I think we need to start teaching our children about emotional wellness.

Children should know as much about their emotional health as they do their physical health. If you ask a 10 year old what being healthy means, they can tell you: eat five-a-day, exercise, and get plenty of sleep. But what if we ask them what emotional health is? Do they know about that?

Statistically, in a class of 30 children, 3 will suffer from a diagnosable mental health problem.

3 is too many.

So here’s the plan. I’m going to share what I’ve learned from my work as a clinical psychologist, both from the research and from my experiences with children and families. I’ll talk about the useful ways we can teach children about how our brains work, the safe ways to explore about ‘big’ feelings and how we can help them develop emotional intelligence and reduce their risk of mental health problems. If you know of other parents who might be interested in learning this, please let them know about ThinkAvellana too.

But for now, I start my journey by sharing Shawn’s TedTalk with you. He figured out the Happiness = Success equation: the first steps towards a bright future.

http://www.ted.com We believe that we should work to be happy, but could that be backwards? In this fast-moving and entertaining talk from TEDxBloomington, psychologist Shawn Achor argues that actually happiness inspires productivity. TEDTalks is a daily video podcast of the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world's leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes.

Written by Dr Hazel Harrison - Clinical Psychologist